Vesicoureteral Reflux

Pediatric urologists at Georgia Urology have extensive experience in the management of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). In fact, our pediatric urologists were the first in North America to perform a minimally invasive procedure to correct urinary reflux without an incision, hospitalization, or need for pain medicine. The 15-minute procedure, know as Deflux, has changed the lives of tens of thousands of children and their families worldwide by limiting open surgery and antibiotic use. Families travel from all over the US to Atlanta for their reflux treatment.

What Is Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR)?

To understand vesicoureteral (ves-ih-ko-yu-ree-ter-ul) reflux, one needs to understand the normal structure and function of the urinary tract.

The Urinary System

The kidneys clean and filter blood to produce urine. Urine is a liquid waste. Urine travels from the kidneys down the ureters and into the bladder. The bladder holds the urine and acts as a storage tank and when the bladder fills, the wall of the bladder relaxes to hold more urine. The control muscle (sphincter) remains tight to prevent leakage of urine. Once in the bladder, the urine is stopped from going back into the ureters by a valve mechanism. When the bladder gets full, it sends a message to the brain. The brain decides when urination should start. The bladder contracts while the sphincter muscle relaxes allowing the bladder to squeeze all of the urine out.

Kidneys (red), Bladder, Ureters (blue)

VUR seen on VCUG

Reflux

Vesicoureteral reflux is a condition in which urine from the bladder flows back up into the ureter and kidney. It is caused by a problem with the valve mechanism. Pressure from the urine filling the bladder should close the tunnel of the ureter. It should not allow urine to flow back up into the ureter. When the ureter enters the bladder at an unusual angle or when the length of the ureter that tunnels through the bladder wall is too short, reflux can occur. VUR is seen in 30-50% of children with kidney infections.

Vesicoureteral reflux becomes a problem when the urine in the bladder becomes infected. The infected urine easily travels backward to the kidney and can cause a kidney infection and lead to kidney damage. Most children with kidney infections have high fevers and may not eat well or have little energy.

Diagnosis

Vesicoureteral Reflux is usually discovered during an evaluation for a urinary tract infection (UTI) by your child’s primary care provider. After a urinary tract infection, a variety of tests can be ordered.

A voiding cystourethrogram (sis-toe-yu-ree-thro-gram) (VCUG) is an x-ray test where a small tube or catheter is placed into the bladder through the opening where the urine comes out. A special liquid called x-ray contrast is used to fill the bladder through the catheter. When the child’s bladder is full, the child will urinate into a special container while on the x-ray table. While the bladder is filling and the child is urinating, x-rays are taken. A similar test called nuclear cystogram may be used instead of the VCUG. A catheter is placed and the procedure is similar to the above test.

A kidney (renal) and bladder ultrasound is a test using sound waves to look for kidney scarring and to measure kidney size. During the ultrasound, a technologist will rub a warm gel on the child’s belly and back. Then, the technologist will move a device that looks like a microphone in the same areas. Other studies may be used to determine kidney scarring and function.

Treatment

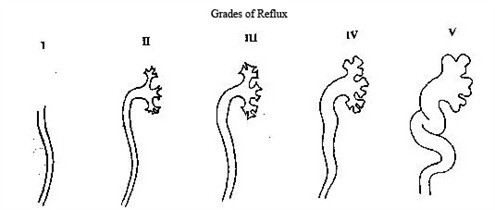

The management of vesicoureteral reflux depends on the grade of reflux, which is determined by the VCUG. Also taken into consideration is the frequency of urinary tract infections, the presence, and progression of any kidney damage, and parental opinion.

Treatment Options for VUR

Antibiotic Treatment

For grades I-III there is a good chance that the reflux will disappear as the child grows and the bladder matures. These children are given low-dose antibiotics daily, to suppress bacteria from growing. Occasional blood tests and urine cultures may be ordered. However, recent evidence suggests that long-term antibiotics may not be effective and may increase bacterial resistance – making antibiotics ineffective. Additionally, long-term radiation exposure from x-ray studies may have risks. For these reasons, surgery may be advocated. In some children with low-grade VUR in whom there have been no further urinary infections, antibiotics may be stopped. Close follow-up is needed in cases of the return of urinary infections.

Outpatient Endoscopic Injection (Deflux) Procedure

A minimally invasive option for patients with grades I-IV is a cystoscopy with an injection of Deflux. This is a procedure where, under general anesthesia, a small telescope is inserted into the bladder through the urinary opening. There are no incisions and there is no need for pain medicine afterward. A gel (Deflux) is injected where the ureters enter the bladder and a little bulge is formed in the bladder wall, preventing the backflow of urine.

After Surgery

After Deflux surgery, there are no limitations and your child may return to school the day after surgery.